Cell Biology 07: Microtubules and Cell Division

These are notes from lecture 7 of Harvard Extension’s Cell Biology course.

Lecture 6 introduced microtubules, and this lecture will discuss their role in cell division. Here is an introductory video:

Overview of the cell cycle

The cell cycle - the process of cell division and replication – is governed by a series of biochemical switches called the cell cycle control system.

The cell cycle is divided into phases that are divided into phases – people will refer to the “4 phases” but then there are actually 5, and people also use other words to group those phases together, and other words to subdivide them. I’ve done my best to summarize the relationship among these terms in the following table. (modified/expanded from Wikipedia):

| MOST general grouping | the supposed “4 phases” | subphases |

|---|---|---|

| non-dividing | Gap 0 (G0) | |

| interphase | Gap 1 (G1) | G1a R G1b |

| Synthesis (S) | ||

| Gap 2 (G2) | ||

| Mitosis | Mitosis (M) | prophase prometaphase metaphase anaphase telophase cytokinesis |

The content of each phase is beautifully summarized in this outstanding Wikimedia Commons image by Kelvinsong:

The fastest-dividing human cells can complete a cell cycle in about 24 hours (G1: 9h, S: 10h, G2: 4h, M: 30 min). Yeast can finish a cycle in 30 minutes, and the fastest-dividing Drosophila cells take as little as 8 minutes.

Master controllers of this process include the cyclins, which regulate cyclin-dependent kinase or CDK. Recall that kinases are proteins that phosphorylate other proteins. CDK’s phosphorylation of its targets allows mitosis to proceed. To be precise, the maturation promoting factor or MPF is an obligate heterodimeric complex composed of cyclin B and CDK, which only does its phosphorylating action when both proteins are present.

Role of microtubules

Microtubules are critical throughout the cell cycle – they organize cellular components and split them in two. Here are a series of videos of the cell cycle which highlight the role of microtubules:

In animals, quiescent cells and even cells in interphase usually have just one MTOC, called a centrosome, which serves as the central hub for all microtubules in the cell. A centrosome is comprised of two centrioles as shown below (thanks again to Kelvinsong):

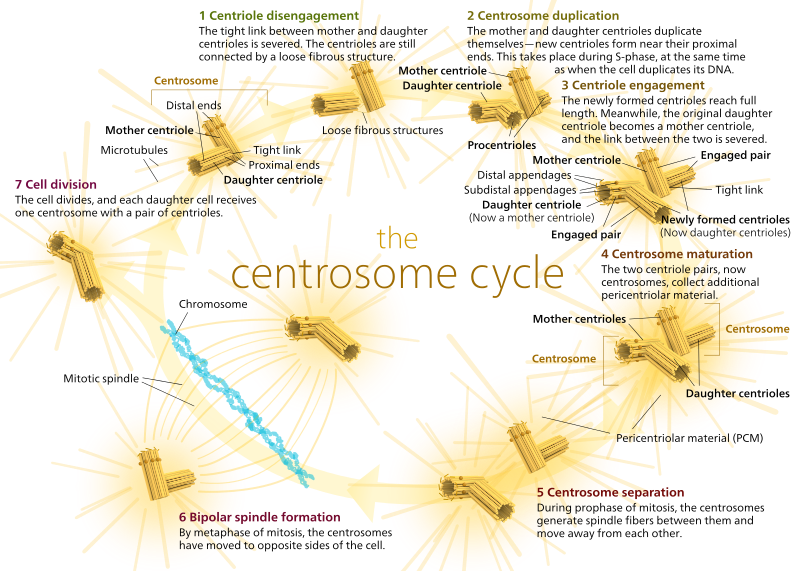

The two centrioles disengage from each other and replicate themselves during S phase, and then separate to form opposite ‘poles’ of the cell during M phase, so that now there are two MTOCs, each of which will eventually be the sole MTOC of a new cell (another boss Kelvinsong image):

During mitosis, then, you have the two ‘poles’ of the cell, each with microtubules anchored at the (-) end and with their (+) ends overlapping, pointing into the center of the cell, as shown here (Wikimedia Commons image by Lordjuppiter):

That whole thing is called a spindle apparatus, and the area where the two MTOCs’ microtubules overlap is called the ‘zone of interdigitation.’ You’ll sometimes hear each MTOC and its urchin-like array of microtubules called a ‘mitotic aster.’

Microtubules during this stage are said to fall into three categories:

- Astral microtubules point outward, toward the cell cortex, in order to anchor the whole spindle apparatus along the axis of cell division.

- Kinetochore microtubules attach to the kinetochore of chromatids.

- Polar microtubules, oriented parallel to each other but in opposing directions, are crucial for pushing the spindle apparatus apart during mitosis. (In fact, polar microtubules are also present earlier and help push the centrosomes apart during prophase).

If you prefer photos over diagrams, here’s what the whole spindle apparatus looks like, with chromatids in blue, microtubules in green, and the kinetochores as red dots:

Microtubules become much more dynamic during mitosis: more gamma-tubulin promotes easier nucleation, but XMAP215, a microtubule stabilizer, is phosphorylated and thus inactivated during mitosis, leaving Kinesin-13 free to catastrophize the microtubules. Fortunes are made and lost quickly. The half life of a microtubule during mitosis is about 15 minutes, compared to 30 minutes during interphase. People study the microtubule dynamics using FRAP: add a fluorescent microtubule, bleach it and see how fast reassembly is occurring based on how soon fluorescence reappears. +Tips also play a major role in aiding and assembling the microtubules.

Kinesin-5 is has two polar heads which bind to opposing microtubules and try to walk towards the (+) end of each. This pushes the two microtubules apart and provides the driving force for the separation of the MTOCs.

Centromeric DNA has low information entropy and special histones that differ from other chromatin. Centromeres are one part of the genome you almost never pick up in next-gen sequencing, even at really high depth. That’s because centromeres are serving a different purpose than much of the rest of the genome: the sequence there is favorable for interaction with centromeric proteins and kinetochore attachment. Cohesins are proteins that keep the two sister chromatids together. We’ll refer to kinetochore proteins as having two layers, the inner kinetochore and outer kinetochore.

During prometaphase, chromosomes move back and forth. Kinesins anchor the chromosomes to the kinetochore microtubules beyond the tip where Kinesin-13 is depolymerizing the microtubules, aided by a shortage of available tubulin dimers. A combination of motor proteins, microtubule interacting proteins and treadmilling serves to move the chromosomes. Meanwhile, dynein and dynactin – motor proteins which walk towards the (-) end – work on the astral microtubules, pulling the MTOCs toward the cell periphery. In metaphase, the chromatids come to be aligned along the ‘metaphase plate’.

During this process the nuclear envelope dissolves and so nuclear import becomes irrelevant. Ran-GEF localizes near chromosomes and generates high concentrations of Ran-GTP which provides energy for some necessary processes (?).

Cells have some mechanism for detecting the tension in the microtubules that indicates their attachment chromatids before mitosis can proceed. Making sure that every chromatid is properly anchored is crucial for avoiding aneuploidy.

By the way, other cytoskeletal elements besides microtubules also play a key role in the cell cycle. In cytokinesis, actin forms a contractile ring and, with the help of myosin II motor proteins, cinches the cell into two.

Importance of model organisms

The discovery of cell cycle regulatory processes relied heavily on some neat features of popular model organisms.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (fission yeast) can exist as haploids or diploids. That’s important because in the haploid phase, one mutation can knock a gene out – you don’t need to hit both alleles. And in yeast, many mutations, especially in the Cdc__ (cell division control) genes, are temperature dependent, where a protein with a missense mutation can still function properly at ‘permissive’ temperatures but loses its native function at ‘non-permissive’ temperatures. This makes it possible to study the knockout phenotype (at the non-permissive temperature) while still having the convenience of being able to easily propagate the organisms (at the permissive temperature). The entire S. cerevisiae genome is available as plasmid libraries, making it possible to screen for which plasmid rescues the phenotype of a given mutant. That is how many of the genes that regulate the cell cycle were discovered.

In S. cerivisiae, budding is part of phase G1, and once the daughter cell reaches a certain size, at a moment called “START”, the two are committed to entering S and ultimately completing the cell cycle. Mammalian cells have their own commitment point called the restriction point or R, in G1, which is analogous to START.

Temperature-sensitive Cdc28 mutants don’t bud at the nonpermissive temperature. The Cdc28 gene encodes yeast’s homolog of our cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) which, when and only when complexed with cyclin, can phosphorylate other proteins to regulate their participation in cell cycle phases. Temperature-sensitive mutants at the nonpermissive temperature get stuck unable to bud and enter the S phase. Instead, they behave like wild-type cells deprived of nutrients: they grow large enough to pass START but then don’t continue.

Xenopus (a kind of frog) proved critical for understanding cell cycle, because its reproduction involves a very large number of cells (i.e. enough starting material for Western blots, etc.) that are perfectly synchronized (i.e. all are in the same phase of cell cycle at the same moment. (Compare to yeast, for instance, where cells will not all be at the same phase at the same time). Also the egg itself is large and easy to work with, and multiple cell cycles follow fertilization. In frogs, eggs begin meiotic division but then arrest at the G2 phase for 8 months while they grow in size and stockpile things that will be needed for growth upon fertilization.

Intermediate filaments

In addition to microfilaments and microtubules, eukaryotic cells also have a host of ‘other’ cytoskeletal proteins called intermediate filaments (IFs). Though more diverse than microfilaments and microtubules, IFs are not just a catch-all term for ‘any other filament’ – rather, they are a group of related proteins. They generally extend through the cytoplasm and inner nuclear envelope, are nonpolar and have no motor proteins associated with them. They have great tensile strength and are very stable, with a slow exchange rate and not much breakdown, though phosphorylation can promote their disassembly. Here are some popular examples:

- Keratins are found in epithelial cells, mesoderm cells and neurons. They provide strength and come in acidic and basic forms. Each can form its own strand, but most IFs consist of two strands – one basic and one acidic, sort of twisted around each other. Hair and nails are made of ‘hard’ keratin rich in cysteine for disulfide bonds which provides the immense strength. Perms and straightening rely on reducing the disulfide bonds, reshaping the hair and then reforming the disulfide bonds. You also have ‘soft’ keratin in your skin.

- Desmins such as vimentin are found in mesenchymal cells (bone, cartiledge and fat).

- Neurofilaments are in neuronal axons and regulate the diameter thereof, which in turn determines the speed of action potential propagation.

- Lamins are both the most widespread and are believed to be most similar to the phylogenetic ancestor of all the other IFs. They provide structural support for the nuclear membrane. They might help space out the nuclear pore complexes and also organize DNA.

Finally, a summary video: