Organic chemistry 02: Nomenclature and functional groups

These are my notes from lecture 2 of Harvard’s Chemistry 20: Organic Chemistry course, delivered by Dr. Ryan Spoering on January 28, 2015.

Molecular orbitals and bonding

Molecular orbital theory relies on the description of electrons as waves. If we think of an electron as being constrained to a one-dimensional box - an oscillation of energy between two points along a line segment - there are distinct, quantized energy levels at which this electron can exist. The lowest energy wavefunction, dubbed Ψ1, inverts zero times, the next level, Ψ2 inverts once, i.e. it has one node, and so on. The probability density is given by Ψ2.

We tend to draw orbitals as circular, but in fact they have infinite support, so if you viewed them in cross section they simply diminish in intensity as you get farther from the center, rather than abruptly ending.

In hydrogen, the 1s is the only relevant description. With >1 electron, the exact descriptions break down, but these are still useful ways of thinking about the electrons.

First, let us consider dihyrdogen (H2) and observe how wavefunctions can be added and subtracted, thus blending orbitals. This process is called linear combination of atomic orbitals or LCAO. The number of orbitals is conserved. When hydrogen A and hydrogen B come together, their orbitals blend in two different ways. In one way, both orbitals are in the same phase, giving rise to constructive interference. The resulting field is rotationally symmetric around the bond axis, and is called σ bonding. In another way, the orbitals are in opposite phase, causing destructive interference and giving rise to asymmetry and a node of zero energy between the nuclei. This is an antibonding or σ* orbital.

Given that these two modes of blending are possible, we determine what will occur when the two hydrogens meet by drawing a molecular orbital diagram. Each rung has “room” for two electrons, and electrons fill the rungs in ascending order of energy. In this case there are only two electrons, so they will both occupy the bonding orbital, leaving the antibonding orbital empty.

Now consider carbon’s atomic orbitals. Carbon has four electrons if it is isolated. If we bring in four hydrogens to bond with it, making methane, which molecular orbitals will they fill? If they fill just the slots that are left empty by carbon’s electrons, the molecule is lopsided. We know empirically that methane is symmetric, so it must be the case that the 2s, 2px, 2py and 2pz orbitals hybridize to form four equivalent sp3 hybrid orbitals.

These each look sort of like a cross between an s and a p orbital - one side is bigger than the other. These four arrange themselves in tetrahedron.

When drawing sp3 orbitals, people often only draw the larger side.

Next time, we’ll learn how hybridization can also be used to describe double and triple bonds, and can be used to predict the shape of molecules.

IUPAC Nomenclature

IUPAC nomenclature for organic compounds is introduced exhaustively on Wikipedia. Here is an overview.

Alkanes

Alkanes, otherwise known as saturated hydrocarbons, are the simplest organic molecule. Their naming scheme provides the basis for the names of all other types of molecules. All carry the suffix -ane to indicate they are saturated.

| # of carbons | name | molecular formula |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | methane | CH4 |

| 2 | ethane | CH3-CH3 |

| 3 | propane | CH3-CH2-CH3 |

| 4 | butane | CH3-CH2-CH2-CH3 |

| 5 | butane | CH3-CH2-CH2-CH2-CH3 |

| 6 | hexane | etc. |

| 7 | heptane | etc. |

| 8 | octane | etc. |

| 9 | nonane | etc. |

| 10 | decane | etc. |

| n | polyethlyene | CnH2n+2 |

Because every carbon is tetrahedral, these look like zigzag lines in space. For instance, decane is:

Cycloalkanes

Cycloalkanes follow the nomenclature for alkanes, but with the prefix cyclo-. Note that for a cycloalkane with n carbons, the molecular formula is CnH2n, different from polyethylene (above).

Alkyl substituents

If a cycloalkane has a single alkyl group dangling off of it, it can simply be named, e.g., methylcyclobutane. Methyl, ethyl, propyl and butyl are labeled -Me, -Et, -Pr, and -Bu for short.

Numbering

Choose the longest possible carbon chain, number the atoms, and consider any side chains to belong to the lowest possible numbered carbon. In other words, due to rotation, there are only such things as 2-methypentane and 3-methypentane; there is no such thing as 4-methypentane.

And because of choosing the longest chain, this is 3-methylhexane rather than 2-ethylpentane.

The order of operations for numbering is as follows:

- Choose highest priority functional group

- Choose the longest chain with the most branching

- Choose the lowest numbering for substituents

Carbon-hydrogen bonds are very stable and non-reactive. Once you get oxygens and nitrogens in the mix, they are more reactive.

Alcohols

Alcohols contain a hydroxy (-OH) functional group. If it is the only functional group in the molecule, it becomes the root and defines the name, resulting in an -ol suffix. Thus:

Amines

When you have multiple functional groups, you have to decide which is higher priority, which is based on something. Below left, the amine is the only group, and takes priority, thus adding a suffix. Below right, the -OH is higher priority, so it gives the molecule its -ol suffix, while the amine gets tacked on as as a prefix.

Halides

Molecules containing halogens (F, Cl, Br, I) are halides. These are always substituents and never alter the root word. They give prefixes fluoro-, chloro-, bromo-, and iodo-. Here is 2-chloroethanol.

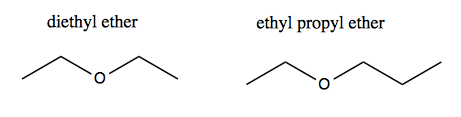

Ethers

An oxygen bonded to two carbons is an ether. Diethyl ether is the anesthetic commonly referred to as “ether.”