Prion cell biology primer

Prof. David A. Harris of Boston University School of Medicine visited the Broad to give a primer on prion cell biology. Here are my notes. He generously allowed me to include some of his slides as visuals.

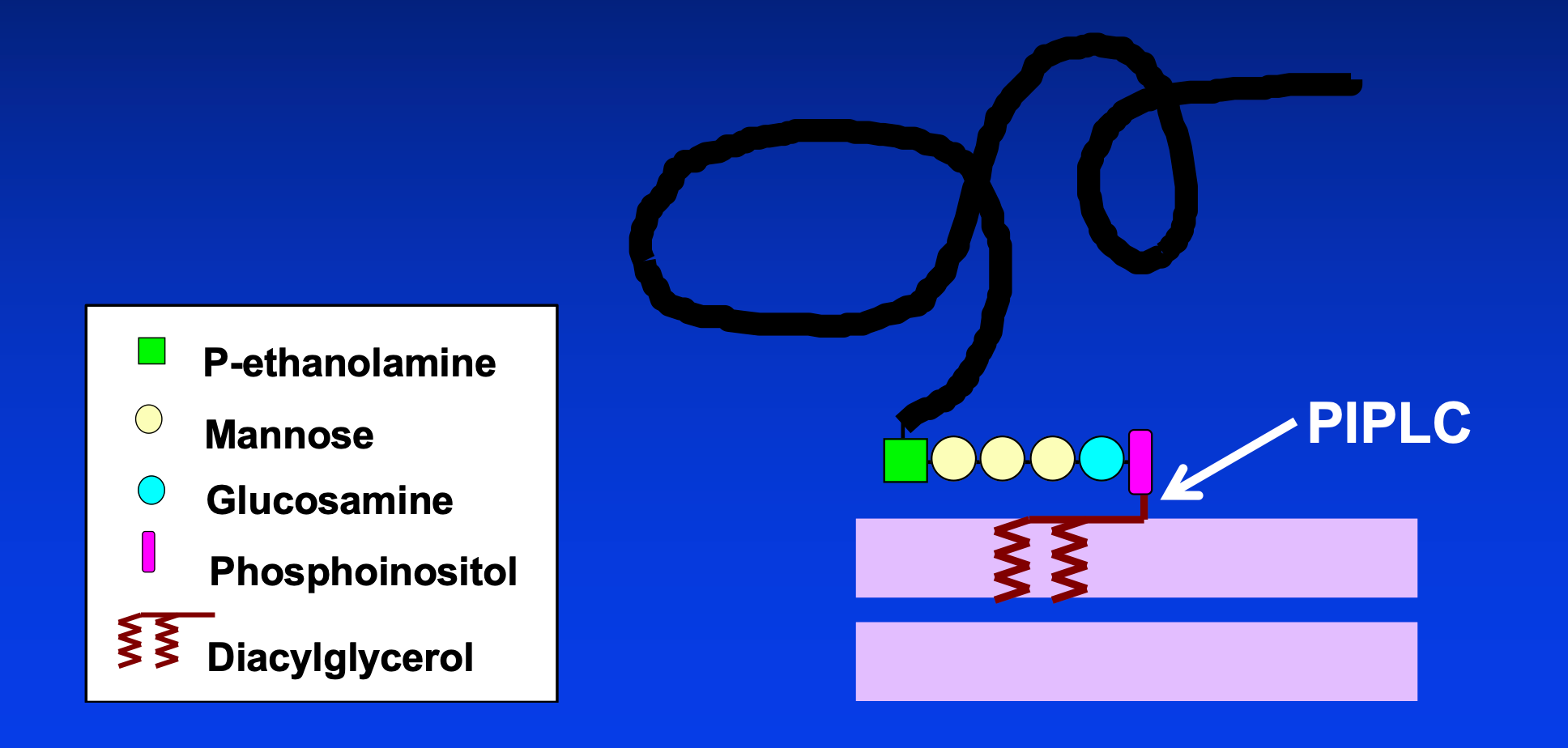

PrP is an extracellular protein GPI-anchored to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. The GPI anchor of PrP has the following structure:

PIPLC, used in the laboratory, cleaves between the diacylglycerol and the phosphoinositol. Endogenous shedding cleaves a peptide bond, removing all of the GPI anchor.

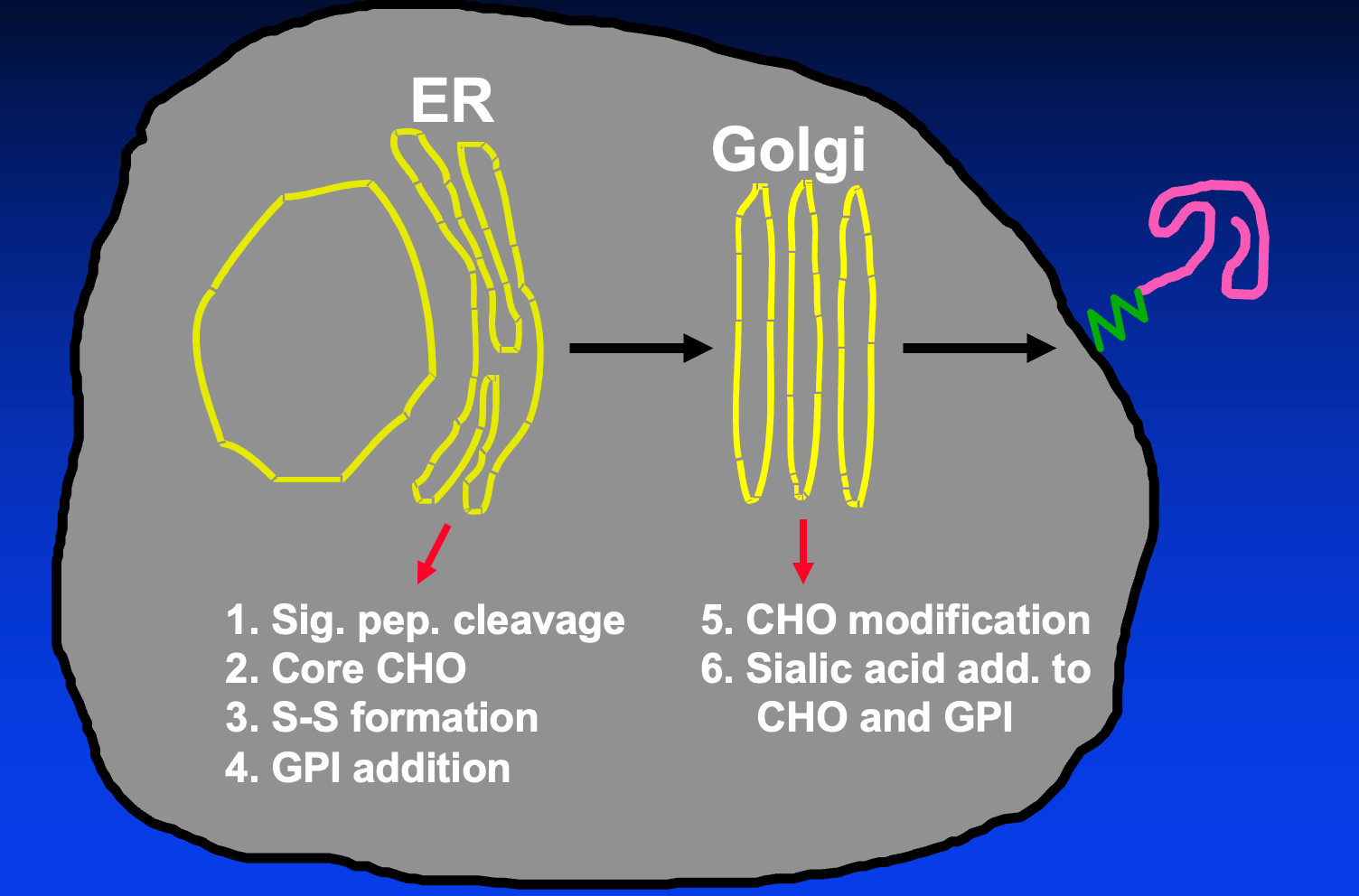

The maturation of PrP occurs across the ER and Golgi:

The N-linked glycans initially attached in the ER are high-mannose, these are trimmed down in the Golgi to yield a mature glycan chain. Sialic acid can be added to both the glycan chains and the GPI in the ER.

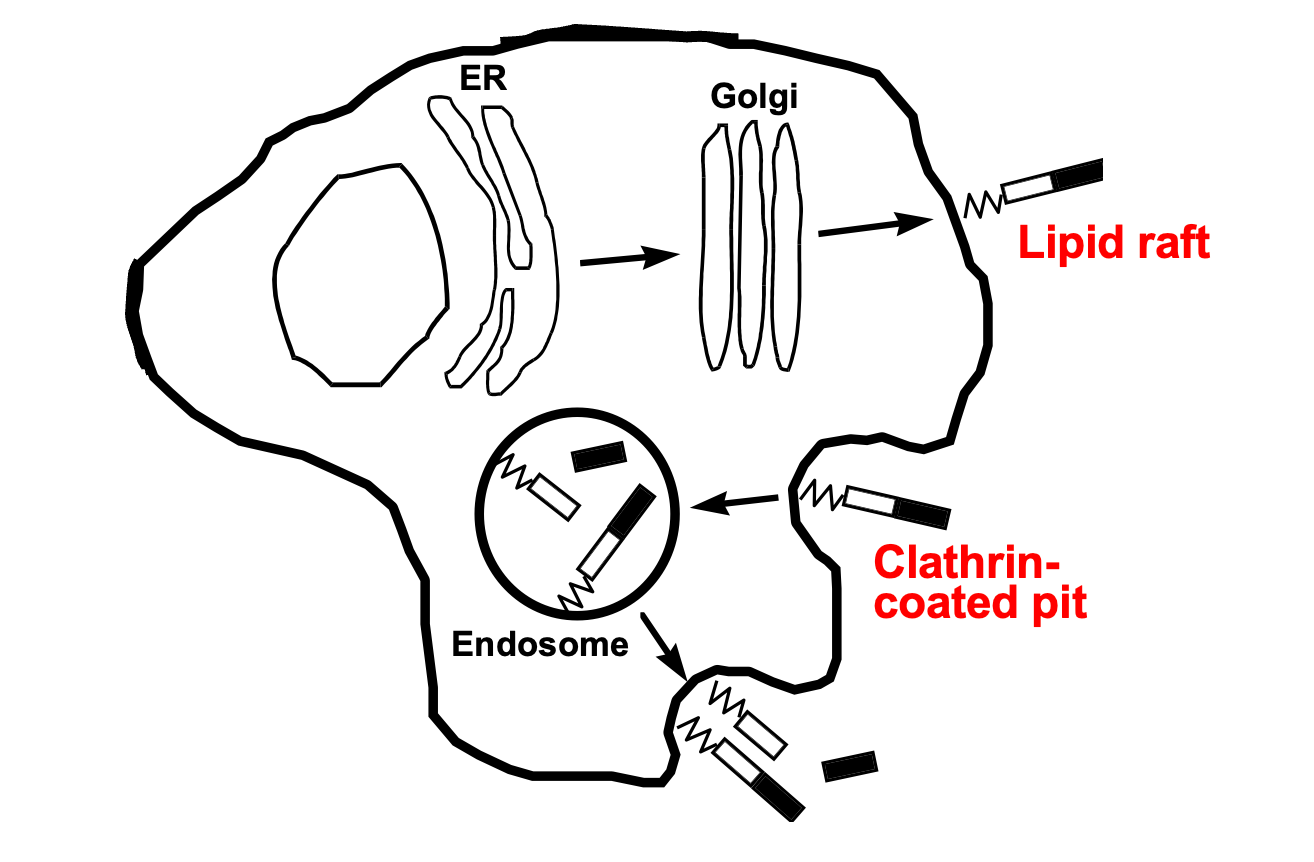

If you extract cells with cold Triton, there are proteins that remain insoluble in this detergent. These were thought to represent distinct membrane domains rich in cholesterol, termed lipid rafts. With high-resolution microscopic techniques you can now visualize these microdomains. They showed that PrP first transits to the surface lipid rafts via the ER and Golgi, then gets endocytosed through clathrin-coated pits into endosomes, where it cycles repeatedly [Shyng 1993]. Usually proteins endocytosed through this pathway are transmembrane and have C-terminal domains that associate with clathrin adapter proteins. Since PrP does not have a C-terminal domain the thought is that this must involve some intermediate protein whose N-terminal domain PrP interacts with, and whose C-terminal domain can interact with the clathrin adapters. Various proteins including LRP and Glypican have been proposed to have this role; there may be others we haven’t discovered yet as well. Some of these turn up in proteomic interactome studies of PrP.

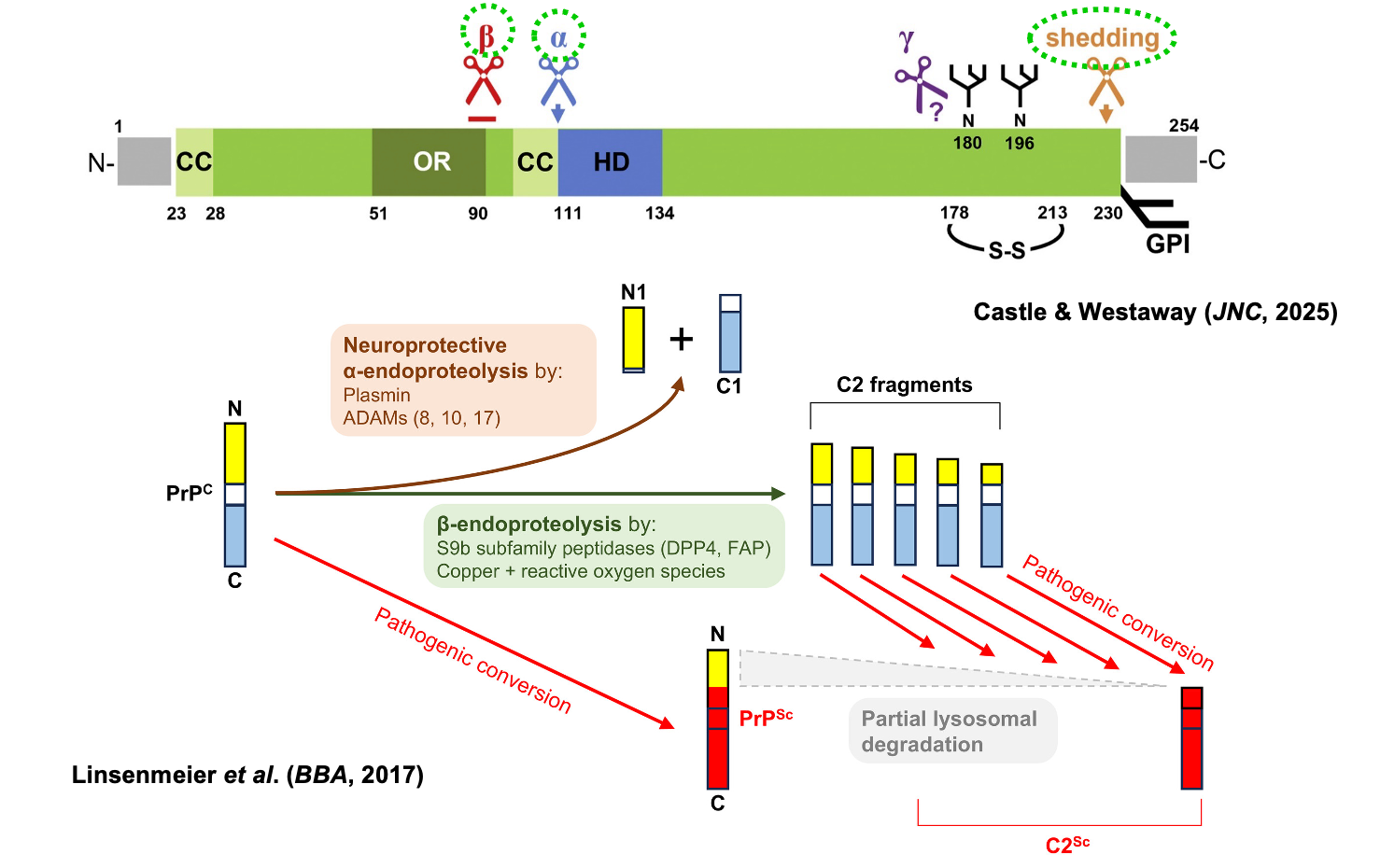

PrP undergoes several different endoproteolytic events [Harris 1993], reviewed in [Linsenmeier 2017, Castle & Westaway 2025].

Above: PrP cleavage diagram comprised of Figure 1A of Linsenmeier 2017 and graphical abstract of Castle & Westaway 2025

In almost any cell where you express PrP — N2a is just one example — or in vivo, you always see a C1 fragment, corresponding to the product of alpha cleavage. Its role / native function is not yet clear. Various ADAMs have been shown to do alpha cleavage, including 8, 10, and 17. Plasmin has also been proposed.

Beta cleavage is less observed for PrPC but occurs for PrPSc, producing the C2 fragment. C2 has multiple exact cleavage sites but roughly corresponds to the same domains which get removed by proteinase K in the laboratory when you treat PrPSc.

Shedding occurs all the way near the C terminus and releases the protein into extracellular space.

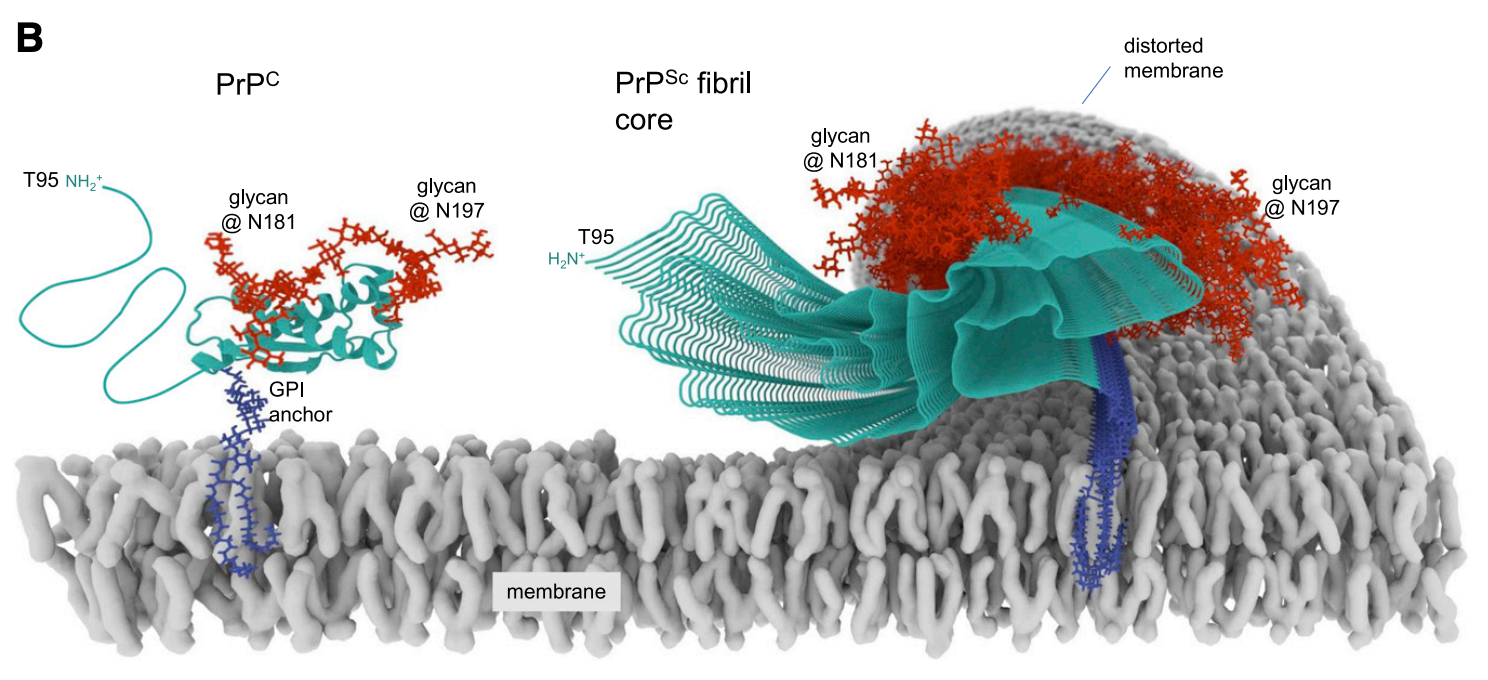

Alison Kraus’s PrPSc structure is a single, twisted protofibril, where each monomer has 11 beta strands, all aligned with each other as a parallel in-register intermolecular beta sheet (PIRIBS) [Kraus 2021]. An implication is that the fibrils are sided — the top and bottom ends look non-identical. This implies they may grow non-symmetrically. Jan Bieschke has done single-fibril imaging to try to gain insight into how they grow [Sun 2023]. PrPSc retains the GPI anchor, thus, the twisting of the protofibril inherently has to deform the membrane, as shown in this Alison Kraus illustration [Kraus 2021]:

Above: Illustration of PrPSc deforming the membrane via its GPI anchors, from Kraus 2021 Figure 4D.

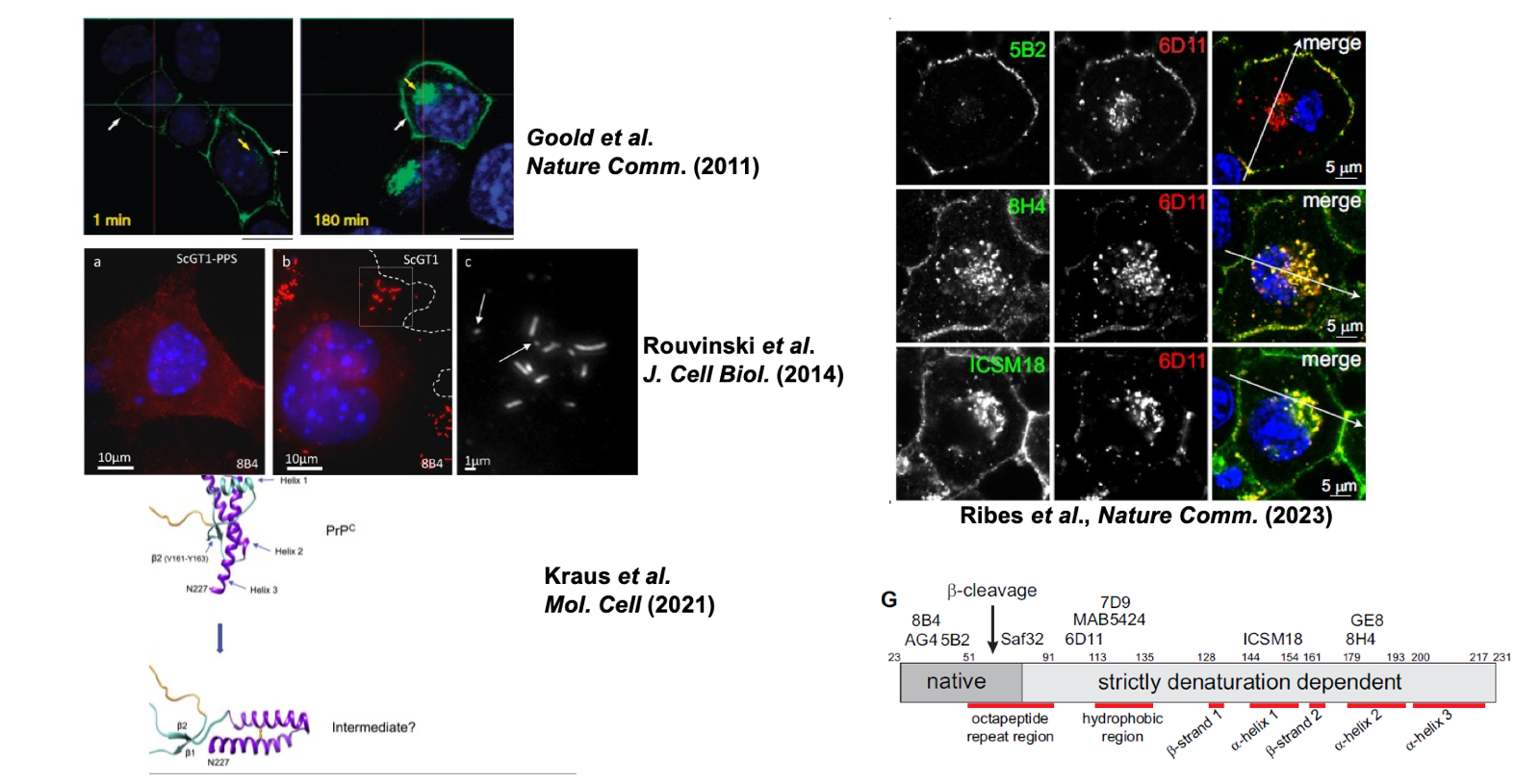

Folks at UCL led by Sarah Tabrizi devised a clever way to figure out how initial infection of cells proceeds. They wanted to image the nascent PrPSc just formed in the cells, without being obscured by the far larger amount of inoculum you used to cause the infection. They achieved this by expressing a myc-tagged, but convertible, PrP in cells. Within 1 minute of applying inoculum to cells, they could already see host cell-expressed PrP forming aggregates [Goold 2011]. An additional challenge is that misfolding buries many of PrPC’s epitopes, thus you need guanidine or proteinase K treatment of fixed cells to expose the epitopes of the misfolded protein (antigen retrieval). You can also use PIPLC treatment, which releases PrPC, whereas on PrPSc the GPI anchor is relatively less accessible and it does not get released. They found that the PrPSc forms first on the plasma membrane within 1 minute, and then a few minutes later some perinuclear compartment lights up [Goold 2011]. It’s not totally clear what that perinuclear compartment is; it might be endosomes or it might be Golgi. Some of the molecules undergo beta cleavage in that compartment. Some uncleaved molecules get recycled back to the membrane, perhaps not unlike how PrPC does. When back at the surface, the PrPSc forms strings along the plasma membrane that Albert Taraboulos’s lab was able to visualize moving on an unfixed live cell [Rouvinski 2014]. Peter Klohn at UCL has also recently used orthogonal methods and reached similar conclusions with really striking images [Ribes 2023]. Antibody 5B2 to the extreme N-terminus recognizes cell surface PrP but does not pick up anything in the perinuclear compartment. In the perinuclear compartment you can only see the PrPSc with 6D11 (not 5B2), and then only with guanidine denaturation. Below are some striking images of these key findings:

Above: Images and diagrams of initial PrPSc formation: Goold 2011 Figure 4A, Rouvinski 2014 Figure 1C, Kraus 2021 Figure 4A, Ribes 2023 Figure 1F & 2G.

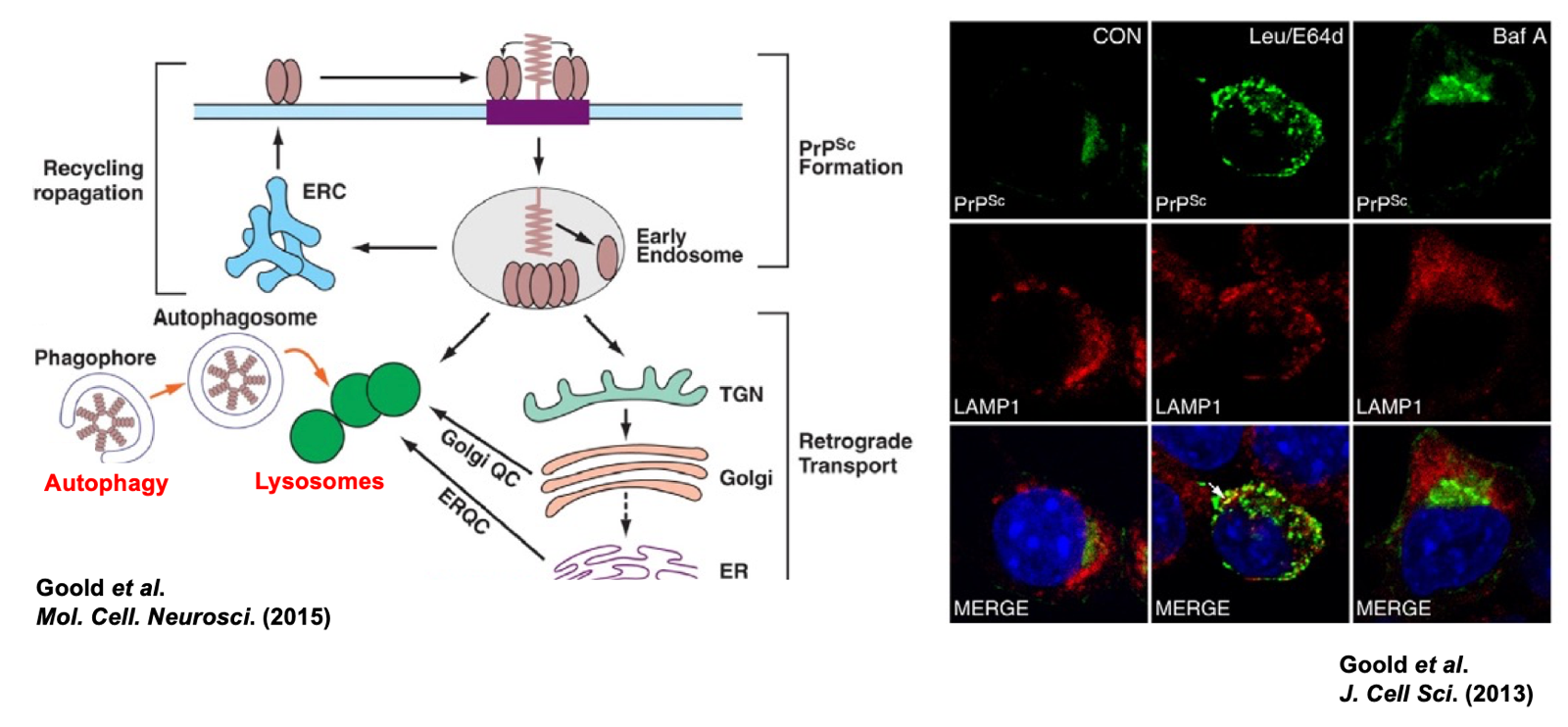

Any protein can be degraded, but PrPSc is degraded incredibly slowly. Even in cultured cells, its half life is days, compared to hours for PrPC. Inhibitors of lysosomal proteases, such as leupeptin, E64, and bafilomycin, block this degradation, confirming that the lysosome is the site of PrPSc degradation [Goold 2013]. The current best thinking is that once PrPSc is internalized into endosomes, a subset of it goes to endosomal recycling compartments (ERC) and returns to cell surface, whereas other molecules of PrPSc undergo retrograde transport to the trans-Golgi network and eventually Golgi, while still others stay in endosomes that mature into lysosomes. The perinuclear compartment observed in the above cell culture studies could correspond to one or more of these.

Above: Pathways of prion degradation. Goold 2015 Figure 1 and Goold 2013 Figure 6B.

For decades, the holy grail of the prion field was to figure out the structure of PrPSc which was finally accomplished in the past few years [Kraus 2021] and has since been achieved for a few additional prion strains. Prion strains differ in their clinical phenotype [Bessen & Marsh 1992], neuropathological patterns, degree of accumulation on neurons versus astrocytes [Carroll 2016], glycoform preference, and the amount of guanidine required to denature them. All this suggested that they must be different molecular structures, which has finally been confirmed by cryo-EM in the past few years.

They found years ago that various PrP mutants, if transfected into cells and overexpressed, acquired limited protease resistance (they are less resistant than PrPSc, being degradable by a lower amount of PK) [Lehmann & Harris 1996]. They are PIPLC non-releasable and retained in the ER [Ivanova 2001]. This is reflected in for instance the PG14 mice, where the mutant PrP acquires many of the properties of PrPSc without actually being infectious [Chiesa 2003]. In neurons induced from iPSC from E200K carriers, however, they did not find detergent resistance, PK resistance, or RT-QuIC seeding activity [Gojanovich 2024].