CRISPR: isn't that your problem solved?

At the CJD Foundation conference in summer 2014, one member of an affected family stood up during a Q&A session and asked, apropos nothing in particular from the lecture that had just wrapped, “But what about CRISPR? If we can edit DNA, isn’t that your problem solved?”

It was a good question! I loved that someone asked it because it was the elephant in the room. Here’s a hotel conference hall full of people with a deadly mutation in their DNA hearing all day from scientists that there’s no treatment or cure, while the news is saying we now have the ability to edit DNA. And I loved it because it was a question I had only just gotten my head around months earlier too. It was only in the previous 2 years that scientists had figured out how CRISPR works and gotten it to work in mammalian cells [Jinek 2012, Cong 2013]. It was that nascent stage where everyone knew there was a lot of possibility, but the limits of that possibility were fuzzy. Or at least, they were fuzzy to me, because I was new to science.

CRISPR is a programmable bacterial tool that can be used to cut, bind, or edit DNA. What I had figured out by 2014 was that the main reason this wasn’t “your problem solved” was delivery. A CRISPR system is not a small molecule that you would take like a pill; it’s a big old RNA-protein complex that needs to get into cells, and into the nucleus of cells, to do its job, and cells don’t like just letting anything in. An adult human has 100 billion neurons. Getting some kind of CRISPR therapeutic into all of them is was, in 2014, a very, very unsolved problem. There were other problems too. Will it create other unwanted changes in DNA around the targeted site? Will you have an immune reaction to CRISPR? Will it mess up other parts of your genome elsewhere in your DNA and cause cancer? And so on.

But all of these are problems one can begin to try to solve, and a LOT of people were working on solving them.

A couple years later, Ben Deverman engineered the first viral vector that could get DNA into, not all, but a majority of neurons in the mouse brain [Deverman 2016]. It later turned out that vector, called AAV PHP.B, would never work in humans, but 8 years later he developed an AAV that looks like it may actually work in humans [Huang & Chan 2024]) In any case, no one knew at the time that PHP.B was going to work only in mice, and the ability to deliver DNA into neurons suddenly made it possible to think about putting the DNA encoding a CRISPR system into an AAV, in order to edit DNA in the brain. In the same year, David Liu engineered the first base editor, a way to use CRISPR not to cut DNA, which risks creating random edits you don’t want, but to replace a specific “C” with a “T” [Komor 2016]. So much suddenly seemed possible!

Sonia and I were responsible for none of the above advances, but we were in the right place (the Broad Institute) at the right time (to be precise, July 12, 2016, at 3:22 pm), when David Liu contacted us to ask if we’d thought about editing the PRNP gene to correct Sonia’s mutation. By this time we were PhD students, and we’d thought deeply about therapeutic strategy in prion disease. We were working with Ionis on the ASO knockdown strategy and had thought a lot about the clinical development path for that drug. We had a lot to say. What I proposed to David that day, and I’ve made this same argument time and again to patients and family members, journalists, NIH study sections, neurologists, and many others, is that if we have the ability to edit DNA, what we actually want to do is knock out PRNP altogether, and not just correct a mutation. There are 4 reasons for this.

- Wild-type PrP is still fuel to the fire. Yes, mutations like Sonia’s D178N start the fire (meaning, misfolding of PrP) in genetic prion disease, but once it starts, the other copy, the patient’s normal PrP (at least in some patients some of the time), also contributes to the disease. So if you’re not lucky enough to correct a mutation before the first prion misfolds, you may be too late.

- Most patients don’t have a mutation. Genetic prion disease is our best shot at prevention, but 85% of newly diagnosed cases are sporadic, meaning, there’s no mutation to correct.

- One drug to rule them all. We’re already a rare-ish disease, so subdividing and needing a separate drug for each mutation is going to make it vastly more difficult to develop a safe and effective drug.

- Figuring out whether you did it. Our quest is not like sci-fi/fantasy quests where there’s an epic battle climax and then you just know you’ve won. No one ever develops a bioanalytical assay to confirm whether Voldemort is finally dead. But in biomedicine, in parallel with developing drugs, we spend an absolutely enormous amount of energy trying to figure out whether drugs actually do what they’re designed to do. Seeing whether a drug makes people live longer takes a lot of time and requires exposing a lot of patients to a potentially risky new drug; before taking all that risk, you want a quick way to check whether the drug even does its job in the first place. For PrP lowering drugs, we can measure CSF PrP to figure out if we lowered it. If we edit the DNA to correct a mutation, we’d need an assay to test whether that one specific amino acid in PrP is changed in the patient’s CSF. That means a custom mass spec assay, which depends on having a good peptide around that amino acid that you can measure. It may be possible, but it’s technically far more challenging than just measuring CSF PrP, it would need to be customized for every mutation, and for some it may be impossible.

Based on the above, I asked whether David’s editors could install the R37X variant, a premature stop codon that knocks out the PRNP gene and that we had just found naturally occurring in a healthy human [Minikel 2016]. David wrote back at 5:39 pm:

If my analysis is correct… I think base editing PRNP R37—>X is an ideal site for our current base editors

By 9:56 pm, David had introduced us to the people on his team who had just figured out how to package a base editor into AAV, and they set about designing editors for R37X with the goal of eventually testing them in mice.

9 years later, we published a paper showing that it worked [An & Davis 2025].

This 4-orders-of-magnitude contrast in time scale is a microcosm of biomedicine. Ideas can be beautifully simple and elegant. Reducing them to practice is messy, error-prone, uncertain, expensive, and can almost always be improved.

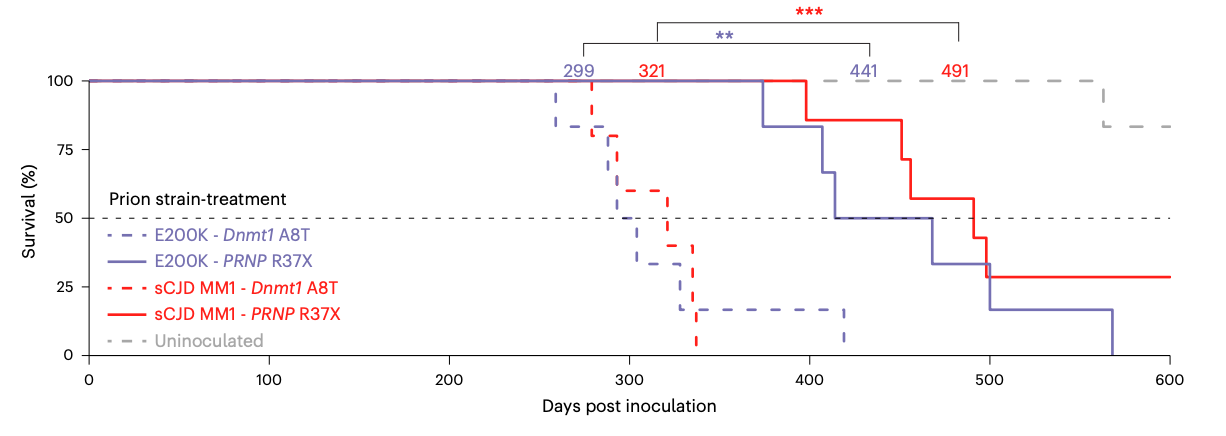

Over the course of that 9 years, Jessie Davis and then Meirui An spent countless hours developing a base editor and then iteratively improving every piece of it. In time they would test a total of 56 different versions. In the meantime, using the earliest and crudest functional version of the editor, we launched a 600-day survival study in humanized mice. We waited, and waited, and waited. I was initially blinded to treatment group, and I still remember the day, about a year in, after half the animals had died, when Jessie called me into David’s office for a reveal. The half that were dead were the all but 1 animal of the untreated group. All the treated animals were alive. The editor worked.

9 years is enough time for a lot of perspectives to change. Now that we know of at least 2 cases of occupationally acquired prion disease [Brandel 2020, Casassus 2021], I no longer believe the scientific knowledge gained from inoculating humanized mice with human prions — at least to test the now-established therapeutic hypothesis of PrP lowering — outweigh the risks. That’s why we didn’t do a second survival experiment with the new-and-improved editor we reach at the end of this paper, even though it gets a higher percentage editing at 1/7th the dose of the original editor. It’s also why we haven’t done humanized mouse survival experiments for divalent siRNA [Gentile 2024] or anything else we’re working on right now. For some modalities, we can do mouse surrogate compounds, such as the mouse Prnp-targeting divalent siRNA that we used in lieu of our human PRNP-targeting drug candidate [Gentile 2024]. But for R37X, we rely on the codon being CGA (= R, arginine) so that we can turn it into TGA (= stop); in mouse, codon 37 isn’t even CGA in the first place, it’s CGG — so no mouse surrogate was possible.

As blogged previously, being able to actually deliver therapies like this to the brain used to be a pipe dream. The mouse studies in our new paper used AAV PHP.eB, an engineered virus that uses a mouse receptor to get into the brain — a receptor that humans don’t even have. But the advent last year of engineered viruses to bind human receptors means that we can now imagine making a therapy like this a reality. Still, those viruses are brand new, and they have yet to have their first clinical proof-of-concept, in other words, we know in a laboratory setting that they bind a human receptor, but how they work in humans is still to be determined. The base editor, as currently designed, requires two separate viruses, each containing half of the editor, to be fused inside the cell: a dual vector system, it’s called. That means that if your virus can reach 60% of brain cells, then perhaps only 60%2, or 36%, of brain cells will get both halves in order to yield a functional editor. A dual vector system would be a risky and challenging first application for a new viral delivery system that hasn’t yet proved its mettle, and making two batches of virus would be an extremely expensive, technically complex and high-risk manufacturing undertaking. So for now, we believe there’s more work to do on these editors before we’re ready to make a drug out of it.

Still, we can’t wait for the disease to be cured before we celebrate. Sometimes, you look back and realize you’ve come a long way, and that there’s clear progress worth sharing with the scientific community. In this study we learned that PrP lowering slows prion disease in a humanized mouse model, and we learned how to engineer and deliver highly efficient base editors for the CNS. It’s an important new step on our journey forward.